Customers Included: How to transform products, companies, and the world – with a single step (Second Edition)

By Mark Hurst

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PART 1: THE CUSTOMER

Chapter 1: The cost of ignoring the customer

Why the border fence failed • What Netflix learned from Qwikster • Customers and disruption

Chapter 2: Innovation missing one ingredient

The Playpump vs. the bush pump • Innovation and the “spaghetti method” • Google Wave

Chapter 3: Starting with the customer experience

When customers aren’t right • The flop before the iPhone • Steve Jobs’ riskiest moment

PART 2: THE METHOD

Chapter 4: What customers say

Focus groups and the hypothetical • Walmart’s misguided surveys • About personas

Chapter 5: Users and tasks

Ford’s troublesome touchscreen • Why B-17s kept crashing • Why usability is limited

Chapter 6: Unmet needs

A better patient experience • How Prospect Park was saved • Iterating with Lean

Chapter 7: What customers do

Why empathy matters • The Gateway listening labs • How to judge any method

PART 3: THE ORGANIZATION

Chapter 8: The cost of ignoring the organization

Complaining about American Airlines • A problem at AcmeCare • How to influence a decision

Chapter 9: Convincing the team

A lesson from “Gunfire at Sea” • The annoyed customer • Motivating the team to act

Chapter 10: The role of leaders

Danny Meyer and hospitality • Why good leadership matters • What a company is for

Recommended Reading

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

Introduction

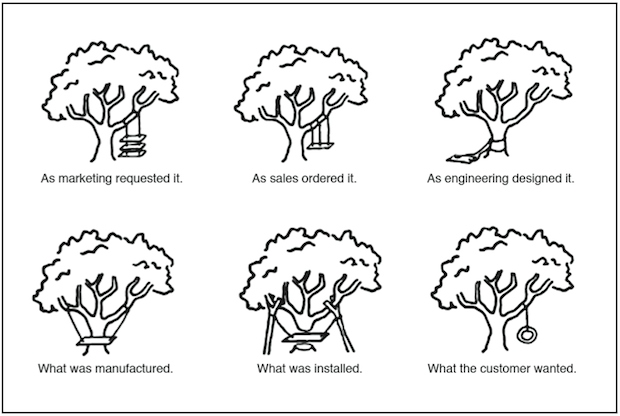

Why do companies so often fail to give customers what they want? The problem is depicted well in the cartoon shown below.The company pursues a series of unwieldy, unworkable ideas while overlooking the customer’s desire for a simple, effective product. The problem could have been avoided, the cartoon suggests, had the company just listened to the customer.

What that might mean in practice is hard to say. How, exactly, is a company supposed to “listen” to its customers? Isn’t it the case that customers often don’t know what they want? And even if a company did somehow figure out what customers wanted, what would be the next step?

This book responds to those questions by describing a new way for companies to create products, services, and strategies. I call it “customers included,” and it makes one simple but radical proposition: When making a decision that affects customers, it’s better to include customers in that decision, in some meaningful way, rather than completely ignoring them.

It may not seem that there needs to be an entire book written about this idea. After all, what executive plans to ignore customers in a major strategic decision he’s about to make? What product manager seeks to leave customers out of the design process as her team develops a new app?

And yet it happens. People appreciate the cartoon on the left because it rings true. After 18 years of consulting to hundreds of companies, I can tell you that ignoring customers is hardly a rarity in the business world. To the contrary, it’s the standard way decisions are made and products are created - in every industry, every geography, and every market. There are exceptions, of course, and several are spotlighted in this book. (What’s more, the exceptions tend to become the top performers of their industries.) But to most organizations, the “customers included” worldview is anything but business as usual.

It’s very important to clarify, however, that this is not a call for companies to become “customer-centered.” As popular as this buzzword is, I’ve never found it to be very realistic. Customers are vitally important but they’re not the center of the company. Executives have many other concerns - new technologies, competitive threats, market trends, internal politics - to weigh when charting the organization’s strategy. Customers are one of many essential inputs to any significant decision.

But even though customers aren’t the center, they also should not be left out of the process entirely. This is where many companies have erred. Concluding (correctly) that it’s impossible to be customer-centered, some executives have settled on the other extreme and stopped including customers at all. When I ask why, I usually hear one or more of the following:

• There’s not enough time in the project to spend with customers.

• Customers don’t know what they want.

• We already know what customers want.

• Customers aren’t designers, so we shouldn’t ask them to design the product.

• First we need to launch our product, and then we’ll find out what customers think.

It’s not hard to empathize with each of these. Time is often short, teams often already know what they want to build, and customers indeed should not be asked to design (that’s the team’s job). But none of these factors should prevent the company from including customers. Customers are an essential, not optional, component in the decision-making process. Leaving them out, as we’ll see in a number of case studies, can have serious consequences.

Fortunately, there are organizations today that demonstrate a different approach. They create new products, and new strategies, with customers included - not as the center, but as one of several essential ingredients in the process. These organizations have dramatically improved the customer experience in fields as diverse as health care, banking, travel, restaurants, Internet services, urban design, global development, and consumer technology. These case studies, all of which are covered later in the book, point to the effectiveness of this one simple idea: by including customers, organizations can dramatically improve the odds of success for any service, product, innovation, or strategy.

Note that this book uses the word “customer” in a broad sense, denoting anyone on the receiving end of a product, service, or other experience. The customer could be a shopper, a user, a student, a patient, a citizen, or even an employee using an internal service. Every product, every service, every mobile app and website, every innovation of any type has customers. (The use of the word “customer” in this way goes back to 20th century management theorist and author Peter Drucker, about whom I’ll say much more, later in the book.)

In all cases, including customers requires three basic steps:

• Observe customers directly.

• Discover customers’ key unmet needs.

• Build consensus across the organization to meet those needs.

The book is roughly organized around those three topics. Part 1 covers customers, Part 2 covers research methods (with special emphasis on discovering unmet needs), and Part 3 discusses the organization.

This book is intended to help organizations and teams create better products, services, and experiences for their customers. CEOs, executive directors, general managers, and other leaders are my primary audience, since they are best positioned to change their organizations - and industries - for the better. Product managers, designers, marketers, technologists, and students preparing to take on these roles can also learn from the case studies within these pages.

About Creative Good

Creative Good is a consulting and services firm based in New York City. When I founded the company in 1997, very few people were talking about customer experience; since then, Creative Good has pioneered the discipline and is a world leader in the field. Today, we still maintain our strategic perspective of improving business by improving the customer experience. Part strategy, part organizational development, and part user experience design, our “customers included” worldview remains unique - and uniquely powerful.

Over the past 18 years, Creative Good has worked with hundreds of companies, observed customers on five continents, and developed customer experience strategies for banks, retailers, media companies, and social networks. We’ve even helped rethink the visitor experience of a city park (more on that later).

After working with this wide range of clients, I can report that the “customers included” approach is universally effective: by observing customers, finding out what customers want, and building organizational consensus, we help our clients deliver the right solution. Whether an organization wants to achieve better innovation, higher profits, or some other measurable outcome, including the customer leads to success.

It’s worth acknowledging upfront that including customers is hard work. There is no trendy idea or framework that will magically solve the challenges that companies face. The “customers included” process is simple to describe and easy to understand, but it requires real commitment from the team to see the results. With the right people on board, teams can generate incredible results, as I’ll describe in later chapters.

First, however, I’ll describe what happens - all too commonly - when an organization makes a strategic decision without including the customer.

Chapter 1: The cost of ignoring the customer

“It’s a huge mistake.”

The driving distance from Los Angeles to Chicago is just over 2,000 miles, requiring about 30 hours to complete. The border between the United States and Mexico, stretching from Tijuana to the Gulf of Mexico, is about the same distance. Securing a national border of such massive length is difficult and expensive, to put it lightly, as shown by the U.S. government’s many attempts over the years. One recent failure underscores the importance of including customers in the design process.

A few years ago, the Department of Homeland Security launched a project that promised an innovative approach to decreasing illegal border crossings. The Secure Border Initiative, or SBInet, promised to use technology to deliver more effective results, at lower cost, than previous attempts to secure the border. Boeing, having won the contract to build the system, stood to make billions of dollars if the project succeeded.

It was an ambitious idea. In contrast to a physical fence, which had already been tried at great expense, SBInet would be a “virtual fence,” using a high-tech network of sensors, cameras, and surveillance towers to detect crossing attempts. The location of any such attempt would be transmitted to U.S. Border Patrol agents, who would use the data in their ground operations. The effectiveness of the entire system depended on the accuracy of the data and the Border Patrol agents’ ability to use it.

An SBInet tower. (U.S. Customs and Border Protection)

Unfortunately, SBInet failed on both counts. When, after numerous schedule delays, a pilot project finally launched on a stretch of the Arizona border, major problems quickly became apparent. The sensors, which had been promised to detect people from miles away, would instead mistake windblown leaves, or even raindrops, for humans. There were more problems in the Border Patrol vehicles, which had been outfitted with laptops for agents to access the sensor data. The laptops, not equipped to work in the dusty environment of the desert, were prone to breakdowns - and even when they were working, Border Patrol agents had difficulty using them while driving on rough terrain.

One might reasonably wonder why the project launched with such obvious flaws. Specifically, why didn’t Border Patrol agents raise concerns about the dust and the bumpy roads before the system was built and launched?

The answer comes from a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report published in early 2008, a little over a year after Boeing began work on the project. The report concludes that SBInet was “designed and developed by Boeing with minimal input from the intended operators of the system . . . The lack of user involvement resulted in a system that does not fully address or satisfy user needs.” Border Patrol agents interviewed for the report said that “the final system might have been more useful if they and others had been given an opportunity to provide feedback.”

The customers, in other words, had not been included. Had they been given a voice in the project before it launched, Border Patrol agents almost certainly would have pointed out that laptop computers are not easily used while driving off-road at high speed.

Citing “serious questions about the system’s ability to meet the needs for technology along the border,” the federal government shut down SBInet in early 2011. Around the same time, in a rare display of bipartisanship, members of Congress from both parties showed their exasperation with the project. This included Arizona’s own senator John McCain, who called the virtual fence “a complete failure.”

Near the end of the project, the TV program “60 Minutes” sent host Steve Kroft to Arizona to interview the head of SBInet, a man named Mark Borkowski. What followed was a surprisingly frank assessment from a government official:

Kroft: I’m just kind of amazed that they’re building this, what’s gonna be a multi-billion dollar system for the Border Patrol, and nobody asked the Border Patrol what they needed or wanted, or what would be helpful . . . that’s a pretty big mistake.

Borkowski: It’s a huge mistake, it’s a huge mistake.

“Huge” is right. By the time SBInet was shut down, the project had cost taxpayers almost a billion dollars. It was an expensive lesson in why customers shouldn’t be ignored.

When SBInet officials were asked why they didn’t make a point of finding out what Border Patrol agents needed, they told the GAO that

there was not enough time built into the contract to obtain feedback from all of the intended users of the system during its design and development.

There hadn’t been enough time to include the customer. And that may have been factually correct: the phases of the project may have been dictated by contracts, timelines, regulations, and other constraints, preventing anyone from sitting down with agents to understand what they needed. It’s unclear who, or what, was ultimately at fault. What’s clear is that a huge amount of taxpayer money was wasted because customers had not been properly included.

Two years later, American taxpayers saw yet another problematic launch, this time of Healthcare.gov. Instead of allowing taxpayers to shop for health insurance coverage, the site presented users with a confusing interface and an endless series of technical problems, including going offline altogether. Congressional hearings held in the wake of the launch revealed that Healthcare.gov hadn’t been tested with actual users until a few days before it went online. (A Medicare official said that this was “due to a compressed time frame.”) Although Healthcare.gov was a very different kind of project from the border fence, the similarities were striking: both were high-profile and expensive government projects that failed to make time to include the customer.

Was the SBInet failure instructive to corporations working to secure the border? Around the time SBInet was shut down, Boeing’s competitor Raytheon presented at an industry conference on border security. Raytheon had bid originally on the SBInet project and lost to Boeing, and it was clearly aware of Boeing’s troubles. The presenter explained that Raytheon’s solution to border security was superior because “Raytheon’s software is capable of not only seeing who’s approaching the border, but monitoring their movements [and] correlating thousands of pieces of ever-changing data.” In other words, Raytheon promised to pack even more technology into the solution than Boeing had. Left out was any indication of whether, or how, Raytheon would fix the central error of Boeing’s system. There was no mention of including the customer.

Netflix’s mistake of “terrific value”

Examples of organizations ignoring the customer are hardly limited to big government programs like the border fence. Even in the fast-moving world of Internet companies, this kind of mistake is surprisingly common. Netflix provides a perfect example of ignoring customers in a key strategic decision.

June 2011 was a peak moment for Netflix. The company’s familiar red envelopes carried DVDs to the mailboxes of millions of subscribers across North America. Customers also enjoyed a growing library of movies and TV shows offered by the company’s online streaming service. Business was growing and the stock price was at an all-time high. Meanwhile, Netflix’s longtime rival Blockbuster had declared bankruptcy. The video-rental chain had long been resented by customers for its late fees - in essence, profiting by punishing customers - and Netflix, the customer-friendly alternative, had won.

Then it all changed. On July 12, 2011, without prior warning, Netflix announced a 60% increase in its monthly subscription price, saying it would “better reflect the costs” of providing the service. There was no mention of any benefit for customers; to the contrary, the higher prices were described as a “terrific value.” The reaction from customers was vociferously negative, and many canceled their accounts in protest. (A more amusing reaction came from Jason Alexander, of “Seinfeld” fame, who appeared in a comic video asking for donations to a “Netflix Relief Fund.”)

A few weeks later, in an attempt to recover from the mistake, CEO Reed Hastings sent a follow-up message to the entire Netflix customer base. This message was even worse than the first. After a cursory apology for “messing up,” Hastings stated that the price rise would stand, and then abruptly announced that Netflix would stop offering DVD rentals at all. Instead, customers would have to open a separate account with a spinoff company named “Qwikster.”

Netflix, long known for its simple, easy-to-use service, was now proposing to make things difficult for customers. Checking the availability of a given movie would now require searching two separate websites with two separate accounts. Combined with the recent price increase, this announcement understandably angered customers.

What resulted was one of the loudest and most sustained complaints from any company’s customers, ever. Torrents of negative response poured out of Twitter, Facebook, and blogs - including Netflix’s own blog, which got thousands of outraged comments. Even “Saturday Night Live” ridiculed Qwikster with a skit showing Reed Hastings announcing several more new names for its service.

Within a month, Netflix retracted the plan for the Qwikster spinoff, writing in a blog post that “it is clear that for many of our members two websites would make things more difficult.” Indeed. Netflix had finally listened to customers, but not before its reputation had taken an enormous hit. Previously seen as a customer-friendly alternative to Blockbuster, now Netflix appeared to be similarly willing to gouge its subscribers.

Why would a company with a spotless reputation voluntarily do something to antagonize millions of customers? Shortly after the Qwikster plan was scrapped, Reed Hastings told a reporter that he had made “a mistake in underestimating the depth of emotional attachment to Netflix.” That’s a fair assessment, though it is important to clarify where that emotional attachment came from.

In the countless research sessions my team has conducted at Creative Good, observing customers interact with mobile apps, websites, and other experiences, I can’t remember a single instance in which someone expressed an emotional attachment to a logo, a color, or a slogan. Instead, customers respond to the benefits they get from the experience. If a company offers a good enough customer experience - in which, yes, the logo and other “branding elements” play supporting roles - then customers may eventually form an emotional attachment to the brand.

This was indeed the case with Netflix. Customers’ emotional attachment came directly from the convenience and ease-of-use of the service. Netflix’s brand was (and still is) fully defined by the experience it creates for customers. Hastings’ mistake may be summed up in a simple rule of thumb: Harm the customer experience and you harm the company.

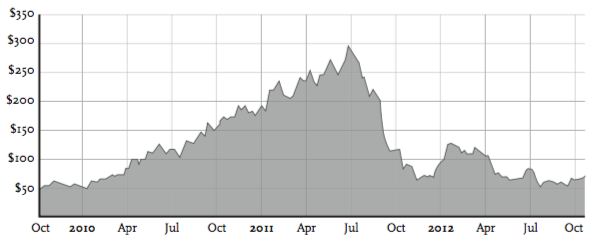

Unhappy with the pricing change and the Qwikster debacle, around 800,000 Netflix customers canceled their accounts in a period of a few months. The company’s stock price also suffered, going from a high of $298 around the time of the first email to a low of $54 about a year later. For both Netflix and the border fence, ignoring customers was an incredibly expensive mistake.

Netflix stock price, October 2009 to October 2012.

An essay by Farhad Manjoo in Slate, however, argued that Hastings had actually made the right decision, despite customers’ overwhelmingly negative reaction, pronouncing that “the problem with customers is that they don’t always know what’s best for them.” Manjoo went on to give Hastings one of the highest compliments in the technology industry, saying his actions were “disruptive.” The idea that innovators should ignore the customer in an attempt to be disruptive is unfortunately a common misunderstanding and bears some explaining.

On disruptive innovation

The term “disruption” was popularized in The Innovator’s Dilemma, a 1997 book by Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen. The book features case studies of several industries, from hard drives to mechanical excavators, that were “disrupted” - that is, transformed by the arrival of radically new technologies.

The history of the technology industry is filled with disruptive change: think of DEC and Wang’s minicomputers being replaced by PCs, or personal digital assistants (PDAs) like the Palm Treo being steamrolled by the Apple iPhone. In each case, the incumbent product would not have been saved by an incrementally better interface - with a higher-resolution screen, say, or slightly better usability. A disruptive competitor reorients the market around itself, while the older product quickly becomes irrelevant.

Christensen suggests that listening to one’s current customers may cause a company to limit itself to “sustaining technologies,” thus preserving its current business while ignoring the larger competitive landscape. Paying too much attention to today’s customers, he warns, could lead a company to avoid the necessary step of disrupting itself to prepare for tomorrow’s market. The inevitable arrival of a disruptive competitor could then be fatal, despite - or even because of - the company’s interest in its customers. As Christensen puts it, “There are times at which it is right not to listen to customers.”

In Netflix’s case, one could argue that the DVDs-by-mail business was under disruptive threat from online streaming. Banishing the DVDs to a (clumsily named) spinoff would firmly establish Netflix’s future as a streaming business. Of course, customers would complain at first - customers naturally resist change - but in time they would come to appreciate the shift. In other words, one could argue, it would be unwise to listen to the customer.

This line of thinking almost killed Netflix. Like the border fence project, Netflix plunged ahead with a strategy that ignored the customer, and it suffered the painful result. In both cases it would have been far better to consider customers’ needs during the decision process. With even a small amount of research, for example, Reed Hastings could have discovered how much customers valued Netflix’s ease-of-use. He could have then formed a strategy of pursuing the disruption (focusing more on streaming) while avoiding the spinoff of a second service, thereby preserving the single, easy interface that customers loved. Instead, Hastings attempted to radically transform Netflix without regard for how it affected people outside the company: a mistake, he said later, stemming from “arrogance based upon past success.” Things might have gone much differently had Hastings considered the customer as an essential input to the decision.

Unfortunately, in an effort to be “disruptive,” many entrepreneurs have concluded that they should ignore customers altogether. This view is largely supported by the business press, which rarely mentions customers when it discusses disruption. For example, the Economist recently described disruptive innovation as “capturing new markets by embracing new technologies and adopting new business models.” It’s no accident that the word “new” appears three times - and that customers aren’t mentioned at all. As disruptive innovation is widely understood, what’s important is that it’s creating something new, not that it’s actually creating a better experience for customers. Ironically, the Economist article goes on to cite Netflix as an example of disruption, in its shift to “streaming on-demand video to its customers.” There’s no mention of how this strategy, as initially carried out, excluded customers and harmed the company.

The current trend to pursue anything that can be called “disruptive” can tempt executives to make high-profile mistakes on par with Qwikster. This is the case made by Jill Lepore in a 2014 New Yorker article, “The Disruption Machine,” in which she explores “what the gospel of innovation gets wrong.” After taking a critical look at Christensen’s original case studies, Lepore concludes that “much of the theory of disruptive innovation rests on [an] arbitrary definition of success,” pointing out that many of the “disruptive” companies praised in the case studies enjoyed “fleeting success” but today are no longer in business - while the companies that were supposedly disrupted by those leaner, more agile competitors are still active and profitable. Along the same lines, strategist Ben Thompson points out that Christensen has repeatedly predicted that the iPhone would be disrupted by cheaper Android devices. As shown by Apple’s record-breaking profits in early 2015, that hasn’t yet occurred. (I’ll cover Apple in more detail in Chapter 3.)

I’m not suggesting that the theory of disruption is invalid, since it does of course occur and can be achieved by smart teams. I merely want to point out that attempts at disruption have a better chance of succeeding when they include the customer. In other words, pursuing disruption by itself is not sufficient to create a winning strategy. One could propose a dozen ways to disrupt any given industry, but without some thought toward the impact on customers, all those disruptive ideas are likely to fail. Companies that aim to be disruptive should include, not ignore, the customer.

Netflix’s recovery

Fortunately for fans of movies and TV shows, Netflix’s missteps weren’t fatal. Instead, Hastings used the crisis as an opportunity to get back to basics and refocus the company on the customer experience. As a result, by summer 2013, Netflix had largely recovered from the crisis, with the stock price advancing past $200 for the first time since the events of July 2011. (As of this writing, in March 2015, Netflix is trading at over $400 per share.)

When asked how he guided Netflix back to health, Hastings said that “there was amazing pressure to come up with the shiny object that would make everything better - but the phrase I used was, ‘There are no shortcuts.’” A “steady and disciplined” focus enabled Netflix to “execute on the fundamentals” - that is, provide a good experience for customers.

Reed Hastings deserves credit for recovering from his mistakes; seeing the world through the eyes of a customer is not always easy. Yet it is vitally important. A team can amass all the money, talent, and technology in the world, but without also considering the customer’s perspective, any innovation risks failure. A good example of this can be seen in the next chapter.

Chapter 1 Summary

This chapter establishes what can happen when organizations ignore the customer. This mistake, and its consequences, can occur in organizations of all types, from government agencies to Internet companies.

Key Points

• It can be expensive to ignore the customer. After spending a billion dollars on SBInet, the government shut down the project - which hadn’t adequately involved the agents who would use the system - and declared it a “complete failure.”

• Netflix paid a steep price for jeopardizing the ease-of-use and convenience that customers so highly valued. The company later recovered by focusing on the basics of the customer experience.

• “Disruptive innovation” can be a helpful framework for understanding a fast-moving competitive environment like the technology industry. However, focusing only on disruptive forces, to the exclusion of concern for the customer, is a dangerous strategy. Even in disruptive environments, it is still essential to include the customer.

Back to Table of Contents